October 2024

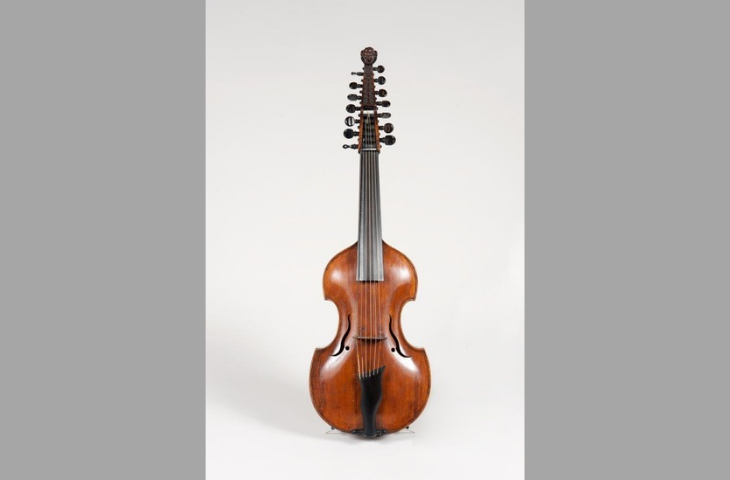

Viola d'amore

Viola d’amore, Johann Rauch, Czech Republic, 1742, inv. 1391-01

Viola d'amore (side view)

Viola d’amore, Johann Rauch, Czech Republic, 1742, inv. 1391-01

Viola d'amore (side view)

Viola d’amore, Johann Rauch, Czech Republic, 1742, inv. 1391-01

Viola d'amore (pegbox)

Viola d’amore, Johann Rauch, Czech Republic, 1742, inv. 1391-01

Viola d'amore (sculpted head)

Viola d’amore, Johann Rauch, Czech Republic, 1742, inv. 1391-01

Viola d'amore (bridge)

Viola d’amore, Johann Rauch, Czech Republic, 1742, inv. 1391-01

About the viola d’amore

The viola d’amore is a bowed string instrument that was most popular during the 18th century. Morphologically, it combines characteristics of both the viola da gamba and violin families, while also possessing some unique features.

Like the viola da gamba, the viola d’amore has a rather large soundbox with sloping shoulders, and its pegbox usually ends in a sculpted head rather than a scroll. Another similarity with the viola da gamba is that the viola d’amore has six or seven melodic strings. Its playing technique, however, is closer to that of the violin and viola: it is held on the shoulder and played without frets. Finally, what distinguishes the viola d’amore from other members of the viola da gamba and violin families are its often flame-shaped sound holes and sympathetic strings. These sympathetic strings run beneath the melodic strings and vibrate in sympathy when the musician bows the upper strings. Their arrangement varies from instrument to instrument; in this case, they pass behind the pegbox, underneath the fingerboard, through the bridge, and are secured at the bottom of the instrument by hitch pins.

History and legacy of the Rauch viola d’amore

Following the viola d’amore’s success in the 18th century, the instrument fell into relative obscurity, but some musicians continued to play it and maintain its repertoire. This viola d’amore (inv. nr. 1391.01) is one such example. It was built in 1742 by Johann Rauch (c.1690–c.1760), a luthier active in Chomutov, Bohemia. In the 19th century, it belonged to Karl (or Carli) Zoeller (1840–1889), a violinist trained in Berlin who settled in London, where he directed the music ensemble of the 2nd regiment of the Life Guards and authored a method for the viola d’amore.

After arriving at the Conservatoire around 1888, Rauch’s viola d’amore continued to support research into early music. Emile Agniez (1859–1909) even played it during the International Exposition in Brussels in 1888. Today, the museum’s instruments are no longer maintained in playing condition, but Rauch’s viola d’amore is regularly copied and thus continues, indirectly, to let its voice be heard.

Bibliography

- Carli Zoeller, New Method for the Viole d’Amour (the Love Viol), its Origin and History, and Art of Playing it, Londen, J.R. Lafleur & Son, 1885, available at https://doi.org/10.25624/kuenste-1987.

- Victor-Charles Mahillon, Catalogue descriptif et analytique du Musée instrumental de Bruxelles, vol. 3, Gand, Ad. Hoste, 1900, p. 38.

- Malou Haine, ‘Concerts historiques dans la seconde moitié du 19e siècle’, in Musique et société : Hommages à Robert Wangermée, Bruxelles, Les Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 1988, p. 121-142.

- Peter Holman, ‘Performed upon the Original Instruments for which it was Written’: the Viola da Gamba and the Early Music Revival’, in Life After Death: The Viola Da Gamba in Britain from Purcell to Dolmetsch, Woodbridge, Boydell & Brewer, 2010, p. 302-336.