September 2024

Fig.1

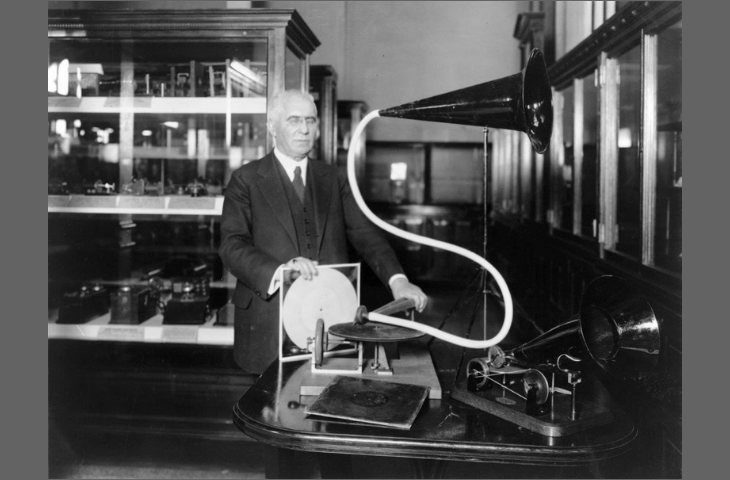

Emile Berliner and his first gramophone (©Library of Congress Online Collection)

Fig.2

78 rpm record His Master’s Voice from the Robert Pernet’s collection : Stan Brenders & INR orchestra

Fig.3

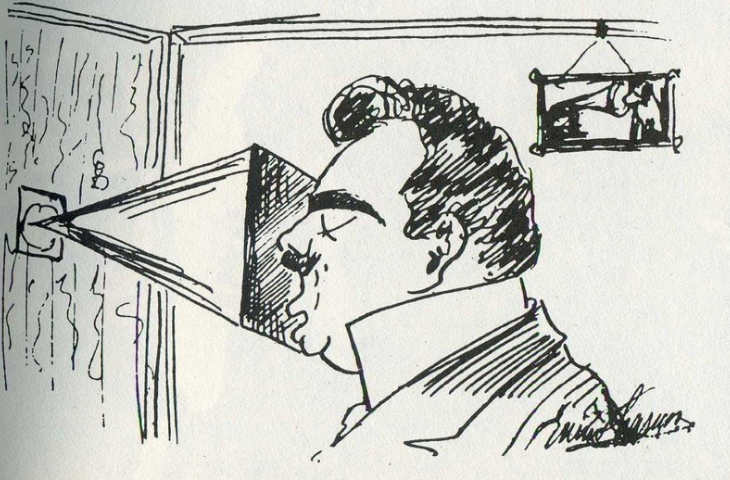

Francis Barraud and his painting « His Mater's Voice » (©Wikipedia)

Fig.4

Caruso singing in a recording horn (©Wikimedia)

Fig.5

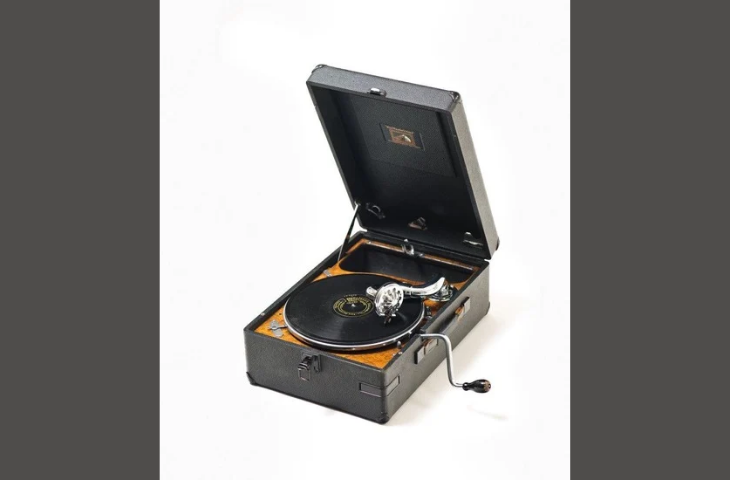

MIM's HMV 102 portable gramophone, Gramophone Company Ltd, Great Britain, ca 1935, inv. 2018.0089 (donation Vincent Verhaeren)

Emile Berliner and the invention of the gramophone

In 1887, the German engineer Emile Berliner (fig.1), who had emigrated to the United States, perfected Edison’s 1877 phonograph and developed the gramophone. The name comes from an inversion of "phonogram," meaning "recording of a sound." The main innovation was to record sound on a flat disc instead of a cylinder. The groove is engraved horizontally, causing the needle to oscillate sideways. Edison was not afraid of this newcomer, claiming that the sound was more accurate and cleaner with the vertical engraving of his phonograph.

The triumph of the disc

The public had many reasons to prefer discs to cylinders. They were cheaper because they were easier to mass-produce, more durable, easier to handle, easier to store, and could hold up to 6 minutes of music thanks to their two sides - twice as much as an Edison cylinder. Until the end of the 19th century, cylinders and discs coexisted, before the disc gradually became the global standard.

After early experiments with wax and glass discs, records were made from zinc coated in wax, which was then immersed in an acid bath to etch the groove into the metal. However, the metal base created considerable sound interference. From 1897 onwards, these materials were replaced by shellac - a natural plastic made from the secretion of the Asian cochineal insect, resin, and wood dust. Discs were first played at 90 revolutions per minute, then standardised at 78 rpm. Shellac formed the basis of the 78-rpm record industry (Fig.2), until it was replaced in the 1940s by synthetic plastic: vinyl.

His Master’s Voice

With the growing success of records, labels and companies proliferated. The history of the Gramophone Company and its subsidiaries - in both the United States and Europe - was a complex tangle of names, bankruptcies, successes, mergers, and splits. However, the company made an indelible mark with its iconic logo: "His master’s voice", showing a dog listening to the horn of a phonograph as if hearing his master's voice. The image was created by the painter Francis Barraud (Fig.3), moved by Nipper, the Jack Russell terrier of his late brother. After trying to sell the painting to phonograph manufacturers, Barraud presented it to the Gramophone Company in London, who purchased it for the princely sum of £100 (around €10,000 today) - on the condition that he replace the phonograph with a gramophone. It became one of the most recognisable trademarks in the world.

Great voices on record

Another masterstroke by the Gramophone Company was its ability to attract great vocalists who had previously been reluctant to entrust their art to the recording horn. Since these stars were unwilling to come to the studio - the studio went to them! Equipped with recording devices, acid tanks and a stock of matrices, production manager Fred Gaisberg (1873–1951) set off in 1899 to make recordings around the world.

In 1902, he attended an opera evening in Milan, where he discovered tenor Enrico Caruso, who left him speechless. Caruso agreed to record ten romances for the gramophone for a fee of £100 - an astronomical sum for less than two hours of work (Fig.4)! Later contracts and successes far outweighed that initial expense. Until then, most people had never had the opportunity to hear these artists perform live. Who among the general public could afford a night at La Scala or Covent Garden? Now, it was possible to enjoy these great voices from the comfort of one’s living room. The gramophone gradually took pride of place in homes, becoming a piece of furniture in its own right - complete with a large horn and, often, a cabinet to store the records.

The HMV 102

In the 1910s - and especially during the First World War - the first portable gramophones appeared, also called “trench gramophones”, entertaining soldiers at the front. With the rise of the automobile after the war, they became known as “suitcase” or “picnic” gramophones, taken along on family outings or trips with friends.

The HMV 102 portable gramophone was the last fully acoustic and mechanical gramophone to be manufactured (Fig.5). To use it, one would open the case and unfold the tonearm. The crank, stored inside the case, would be used to wind the spring mechanism that powered the rotating platter. Once the disc was in place, the needle was gently lowered, and the magic happened! The vibrations picked up by the needle were converted into sound waves by the diaphragm. The sound then travelled through the tonearm into a conical cavity in the case and was amplified via the opening between the platter and the lid, which acted as a sound reflector (video).

Due to its long production run, the HMV 102 was the most produced of all Gramophone Company products, with very few changes made between 1932 and 1958, when it was finally superseded by the electric turntable. The MIM’s model dates from 1935.

Text: Matthieu Thonon