October 2025

Porcelain cards are a fascinating testament to the history of 19th-century business and advertising cards. Used for professional purposes, they represent the profession of their owner in a highly stylised and artistic manner. True communication tools, they were designed to attract attention and stand out, both through the wealth of information they contain and the opulence of their decoration.

The MIM has a collection of 61 porcelain cards, all related to the field of music: manufacturers, makers, teachers, tuners, musical societies, etc. These cards are a true visual identity card, showcasing expertise and excellence.

Birth, evolution and spread of porcelain cards

Porcelain cards would not exist without two major inventions in the field of graphic arts: a new printing technique, lithography (followed by chromolithography, or colour printing), and a new type of paper, known as porcelain paper.

Lithography was invented by Aloys Senefelder in Munich in 1797. This fast, flat printing process became the main method of reproduction at the beginning of the 19th century. As for paper, the appearance of a new white, smooth, glossy variety (German patent of 1827) was a real revolution. Coated with ceruse, an opaque pigment based on white lead, this paper had the appearance of porcelain, hence its name. Another advantage was that it did not absorb ink, which remained on the surface, allowing for very fine line printing.

Porcelain cards therefore appeared in the second half of the 1830s. Although present in Germany, France, the United Kingdom and the United States, they were particularly popular in Belgium. Numerous printers and lithographers — around sixty in Brussels alone — contributed to the distribution of thousands of these ephemera over a quarter of a century.

Gradually, thanks to chromolithography, black prints were replaced by colour prints, giving rise to highly sophisticated graphic developments. The most luxurious cards were even enhanced by hand with gold and bronze metallic powders. No two coloured porcelain cards were ever completely identical; each was unique.

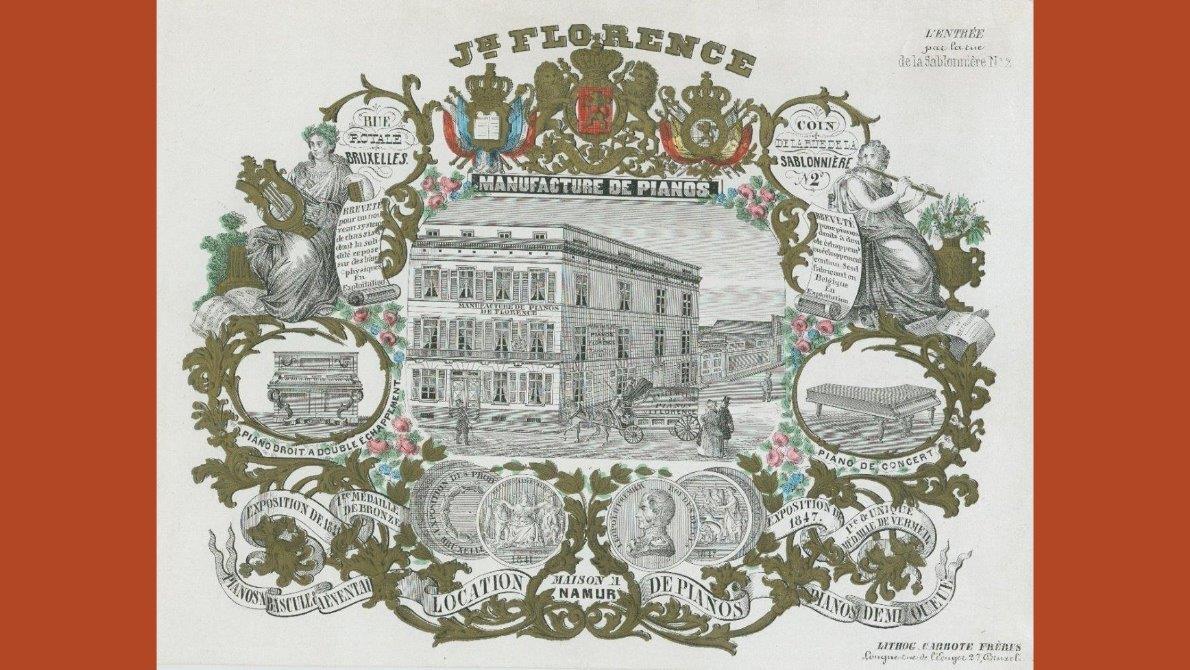

The porcelain card of piano maker Jean-Joseph Florence

The porcelain card of piano maker Jean-Joseph Florence, born in Namur in 1807 and deceased in Schaerbeek in 1868, published by the Carbote brothers, lithographers active in Namur and Brussels, is a remarkable example of visual communication promoting exceptional craftsmanship. This sumptuous card, embellished with gold, reflects the reputation of its owner and highlights the exceptional qualities of his instruments.

It contains a wealth of information designed to promote his business. In particular, it features a highly realistic representation of the building where customers were received, which is especially interesting at a time when photography was still in its infancy and postcards did not yet exist. The card also presents the different types of pianos available for sale, the possibility of renting instruments, and the important patents held by the brand. Finally, it mentions the medals won at the national industry exhibitions in Brussels in 1841 and 1847. The mention of the address of the factory, located at 2 Rue de la Sablonnière, allows us to date the card to 1854, the year Florence moved to the capital.

The decline of porcelain cards

The most prosperous period for porcelain cards was between 1840 and 1865. Although production was intense, it was short-lived, as the use of lead white posed significant health risks. After printing, the cards underwent a finishing process — either rolling or brushing — which gave them their characteristic shiny appearance. This process released tiny particles of white lead, which were hazardous to health, making the manufacture of these cards particularly harmful, especially for printers.

In view of these dangers, the use of white lead was banned, leading to the abandonment of this technique around 1865. Several alternative processes were later attempted to recreate the glossy effect, but none managed to match the brilliance and finesse of the original treatment.

The quality of the printing and the imagination in the typographic decoration make these cards the most exquisite ephemera of this period. They are a precious heritage because, in addition to their aesthetic interest, porcelain cards are a tremendous source of information for the study of a whole section of 19th-century society.

Text: Anne-Françoise Theys

Bibliography

- Bellenger, Rémy, « Papiers et cartes porcelaine », Le Vieux Papier, fascicule 434, 2019, pp. 164‑172

- Bellenger, Rémy, « Le papier porcelaine et ses utilisations, une histoire oubliée », Arts et Métiers du Livre, n° 341, 2020, pp. 54‑61

- De Vos, Thierry, Chromos, les premières publicités / The First Advertising Cards / Le Figurine, le Prime Pubblicità, Armonia, 2007

- Renoy, Georges, Bruxelles sous Léopold Ier: 25 ans de cartes porcelaine 1840‑1865, Crédit Communal, Bruxelles, 1979

- Sorgeloos, Claude, et Jacques Hellemans, « Pour une histoire des techniques et métiers du livre en Belgique : brevets, machines et chimie sous Léopold Ier », Cahiers du Cédic, n° 6/8, 2016