August 2025

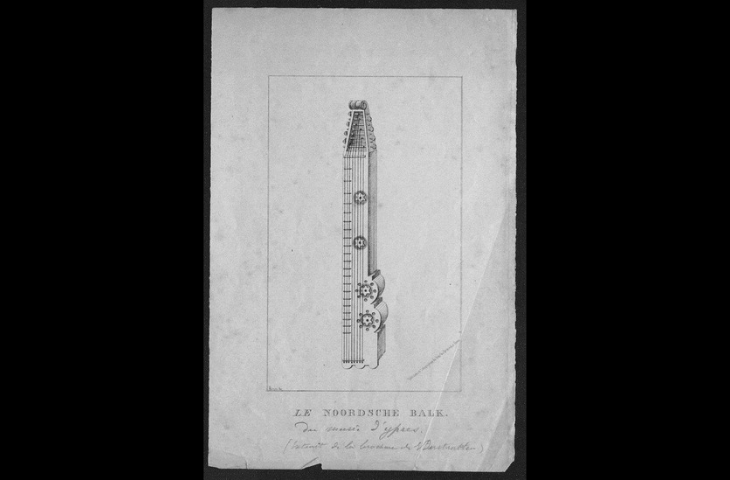

Fig.1

Original model of the dulcimer 2905, Vanderstraeten, Ghent, State Archives, FM 122 no. 59

Fig.2

Dulcimer, Flanders, 17th century, inv. 2905

The hommel: description and function

The hommel (also known as the Flemish dulcimer) is a string instrument with an elongated soundbox. It features a set of melody strings and a set of accompaniment (or drone) strings, all stretched lengthwise from one end to the other. The melody strings are tuned in unison and pass over a fretboard. They can be pressed onto the frets using a small stick, the thumb, or the fingers of the left hand, and are plucked with a plectrum or bowed.

The drone strings are played open and produce a constant note or chord.

The Ypres hommel : history of a lost instrument

This unusually large hommel is a copy of a remarkable historical instrument that was lost during the First World War. The original (fig.1) was kept in the municipal museum of Ypres, located in the historic Meat Halls. The museum and its entire collection were destroyed by German incendiary bombs in late November 1914. (1)

The instrument was spotted in 1865 by the Flemish musicologist Edmond Vander Straeten (1826–1895), who devoted a short monograph to it in 1868: Le Noordsche Balk du musée communal d’Ypres. (2) This was the first known publication about the hommel in Flanders. (3) Apparently unfamiliar with the instrument, Vander Straeten called it a Noordsche Balk ("Nordic beam"), a name likely borrowed from Dutch music historians Klaas Douwes (1668–1722) and Jacob Wilhelm Lustig (1706–1796). (4)

In Flanders, however, the term Noordsche Balk was never widely used. The instrument was more commonly known as hommel, or by other regional names such as pinet, spinet, epinet (from the French épinette), vlier, and blokviool.

The original instrument was donated to the Ypres museum by Father Ferdinand Van de Putte (1807–1882), who served as the parish priest in nearby Boezinge from 1843 to 1858. (5) He told Vander Straeten that the instrument had been used in the past to accompany church singing when the organ was not available. (6) According to the museum label, as reported by Vander Straeten, the hommel was already two centuries old at that time (7), suggesting it dated from the mid-17th century. It may well have been the oldest known hommel from the Southern Netherlands. (8)

The copy by César Snoeck

The copy shown here (fig.2) was commissioned by César Snoeck (1834–1898), a notary from Ronse (Renaix) and an avid collector of musical instruments. He jokingly described himself as suffering from musicorganopathy. Snoeck was a close friend of Edmond Vander Straeten. (9) He likely learned about the Ypres hommel through this connection. The copy must therefore have been made sometime between 1865 and 1898.

After Snoeck’s death, his collection - then the largest private collection of musical instruments in the world - was divided among the musical instrument museums of Berlin, Saint Petersburg, and Brussels. Thanks to the patronage of Brussels entrepreneur Louis Cavens (1850–1940), the Brussels museum was able to acquire the part of the collection related to the Low Countries in 1908: 471 instruments, accessories, and components. (10) Among them were this hommel (inv. 2905) and two other examples (inv. 2906 and 2907). (11)

Characteristics and playing technique

According to the 1903 Ghent-printed catalogue of Snoeck’s collection of Dutch and Flemish instruments, this “large hommel” is an “exact copy” of the original Ypres instrument. (12) But how faithful is this copy?

In his monograph, Vander Straeten compared the original hommel with the Noordsche Balken described by Klaas Douwes in Grondig Ondersoek van de Toonen der Musijk. He observed only one major difference: Douwes’ instruments had three or four strings, while the Ypres hommel had eight - three melody strings and five drones. (13) However, Douwes’ instruments (like all known 17th- and 18th-century European hommels) were diatonically tuned - similar to the white keys of a piano - whereas the copy is fully chromatic, including notes comparable to the black keys. If the original had been chromatic, Vander Straeten would surely have mentioned it. Additionally, he counted 21 frets on the original, while the copy has 29. The drawing included in the monograph also shows exactly 21 frets.

That drawing was made during Vander Straeten’s visit to Ypres by a local artist named Böhm. Vander Straeten described it as “materially flawless.” (14) That may have been an exaggeration: the spacing of the frets in the drawing is unrealistic, and an instrument with such a layout would be unplayable. Moreover, in the drawing, all the frets are of equal length, while the copy includes seven longer frets that extend beneath two or more drone strings. Which version - the drawing or the copy - more accurately represents the lost original remains uncertain.

According to Vander Straeten, hommels were played using two quills: one to press the strings and the other to pluck them. Father Van de Putte specified that a crow’s feather was used as a plectrum. (15)

In terms of construction, the Ypres hommel shares several features with other pre-1900 instruments from the Low Countries: a scroll-shaped pegbox with lateral tuning pegs, six-pointed star-shaped rosettes cut from brass, and a double bulge around the rosettes. A similarly large hommel (134 cm) donated to the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dunkirk between 1840 and 1850 also features a similar double bulge. (16)

With its exceptional length of 151 cm, the Ypres hommel is the longest known example in Europe.

Text: Wim Bosmans and Anne-Emmanuelle Ceulemans

Bibliography

(1) Curiously, this instrument is not mentioned in Catalogue du Musée de la Ville d’Ypres et des tableaux exposés à l’hôtel de ville Ypres, 1883

(2) Edmond Vander Straeten [sic], Le Noordsche Balk du musée communal d’Ypres Ypres: Simon Lafonteyne, 1868

(3) The first subsequent publication on the hommel is by H. [Hubert] and G. [Gabriël/Gaby] Boone, ‘De Brabantse pinet’, in Eigen Schoon en De Brabander 51 (1968), p. 331–337. Hubert Boone also wrote a reference work: De hommel in de Lage Landen Brussel: Instrumentenmuseum, 1976, also published in The Brussels Museum of Musical Instruments Bulletin, V (1975), p. 8–162

(4) Klaas Douwes, Grondig ondersoek van de toonen der musijk Franeker: Adriaan Heins, 1699, p. 118–119; Jacob Wilhelm Lustig, Inleiding tot de muziekkunde Groningen: Hindrik Vechnerus, 1771², p. 82

(5) A. Schouteet & E.I. Strubbe, Honderd jaar geschiedschrijving in West-Vlaanderen (1839–1939) Brugge: Graphica, 1950, p. 100–101

(6) Edmond Vander Straeten, La musique aux Pays-Bas avant le XIXe siècle, vol. 8. Bruxelles: Schott, 1888, p. 202–203

(7) Vander Straeten, Le Noordsche Balk, o.c., p. 2 & 6

(8) The oldest hommel of the Northern Netherlands is a Dutch instrument dated 1608, preserved in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. (inv. BK-NM-5149)

(9) [César Snoeck], Catalogue de la collection d’instruments de musique anciens ou curieux formée par C.C. Snoeck Gand: J. Vuylsteke, 1894, p. III: ‘je trouvai un grand secours dans l’érudition d’un ami de jeunesse, Edmond Vander Straeten’.

(10) Malou Haine, ‘Un mécène du Musée Instrumental du Conservatoire Royal de Musique de Bruxelles, Louis Cavens (1850–1940)’, in Revue belge de musicologie / Belgisch tijdschrift voor muziekwetenschap, 32–33 (1978–1979), p. 208–215

(11) Victor-Charles Mahillon, Catalogue descriptif et analytique du Musée instrumental, vol. 4. Gand: Hoste, p. 426–429

(12) Catalogue de la collection d’instruments de musique flamands et néerlandais formée par C.C. Snoeck Gand: I. Vanderpoorten, 1903, p. 60

(13) Vander Straeten, Le Noordsche Balk, o.c., p. 6. Vander Straeten mistakenly identifies as many melody strings as accompaniment strings: ‘La moitié de ces cordes sonnent à vide, à titre de pédales basses. Les autres sont tendues au-dessus d’un clavier de vingt-et-une touches, et paraissent destinées à exécuter la mélodie.’ This does not match the drawing of the original hommel in the monograph, nor the copy.

(14) Vander Straeten, Le Noordsche Balk, o.c., p. 11

(15) Edmond Vander Straeten, ‘Les récentes publications de la Société du Progrès musical à Amsterdam’, Fédération artistique d’Anvers, 11 November 1882, p. 22, quoted in a manuscript note by César Snoeck, Family archive César Snoeck, Rijksarchief Gent, access number FM 122, file no. 59

(16) Le grand hommel du musée de Dunkerque, http://archivesdufolk59-62.blogspot.be/2013/10/le-grand-hommel-du-musee-de-dunkerque.html; L’épinette du Nord. Cithares à touche du Nord de la France Hazebrouck: Centre Socio Educatif, 1997, p. 133–144