July 2023

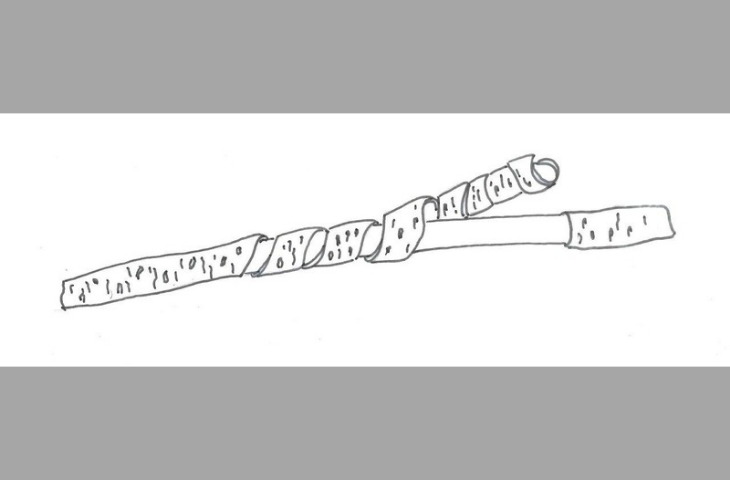

Fig.1

Whithorn, Oxfordshire, before 1897, inv. 1982

Fig.2

Bark rewounded into a cone shape

Fig.3

Oboe, Japan, before 1900, inv. 1811

Wychwood Forest and the whithorn

Situated on the edge of the Cotswolds in south-west England, Wychwood Forest has been a royal hunting ground since the Middle Ages. It once covered a large part of West Oxfordshire. In 1857, by an Act of Parliament, part of it was felled to make way for pastureland. The rest was fenced off a few years later.

With the closure of the forest, certain rights granted to the surrounding towns and villages disappeared. At least since the 16th century, the residents of certain villages were allowed to hunt deer once a year. This event took place on Whit Monday, hence the name whithunt. A few weeks beforehand, the hunt was announced by the sound of whithorns, oboes made from coiled bark and made by youngsters.

A ritual and festive hunt

In some villages, there were more than fifty whithorn players parading through the streets. Around midnight on the night of Sunday to Monday, the villagers were woken again by the sounds of the whithorns. In the rosy light of dawn, in a ceremony known as the peeling horn ceremony, they would gather with the residents of the other villages of the region in the town of Crawley. There, at a place called Chase Green, the whithorns were ritually destroyed before the groups went into the forest.

In the 1830s, this procession was followed by a beer cart. Anyone with a horse, donkey or mule took part in this collective hunt, during which three deer were killed. Following a set tradition, one was for the village of Hailey, one for Crawley and the last one for Witney. The triumphant return of the hunters ushered in a week of festivities, including the famous Morris dances. The following Sunday, the game was cooked and eaten. Obtaining a piece of skin guaranteed a year of happiness, and for young brides the assurance of a wedding within the year.

Making the whithorn

To make whithorn, bark is removed from the branch of a willow tree. The branch is soaked and then beaten to release the bark, which is peeled off in a strip around 27 cm long and rewound into a cone shape (fig.2). The sap, which is still alive, allows the convolutions to adhere to each other, and the base of the resulting cone is secured with blackthorns.

To obtain a sound, a reed must be added. This is a small cylindrical piece of bark detached from a willow twig and set into the thinnest end of the bark cone. Slightly crushed, it forms a double reed known as a trumpet. The reed is not pinched between the lips, but placed inside the mouth. The tone produced by the instrument depends on the length of the cone. The MIM's copy (fig.1) produces approximately a G. But by varying the breath, the musician can also obtain different tones. However, the whithorn cannot be used to play a musical tune. It is a “paramusical” instrument, a noisemaker (see attached sound extract).

Global variations

This type of bark oboe is not only typical of the Cotswolds. It is found in very similar forms just about everywhere in the world, under different names and for different purposes. In Belgium and France alone, it is used for everything from children's games to paraliturgical purposes and as a charivari instrument. In south-west France, it is played at the top of bell towers to call the faithful to church during Holy Week. In other places, it calls villagers to work in the fields or, as in Aubrac, it signals the daily departure of flocks to pasture. The MIM also has a similar instrument from Japan in its collections (fig.3).

The English word whithorn is perhaps derived from the local association of this oboe with Whitsuntide, and more generally with spring, of which Whitsuntide is one of the major liturgical events. It is only at this time of year that the rising sap makes it easy to peel off the bark and turn it into an instrument. It is also sometimes known as the peeling horn.

The MIM’s copy and its history

The MIM’s copy (fig.1) was donated in 1897 by Henri Balfour, the first curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. In the then current evolutionist view, Balfour regarded the bark instrument as a primitive form of the oboe, surviving in a folk environment as it must have been in remote times. By the time Balfour was collecting whithorns, the whithunt had been extinct for nearly fifty years. If a few bark oboes were still made, it was no longer in their original context. Henri Balfour received three from an informant called T.J. Carter, who had had them made by a very old man.

These are probably the three copies still preserved in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. But in 1895 another collector, Percy Maning, probably also linked to Balfour, had three more made by an eighty-year-old ploughman, John Fisher. Victor-Charles Mahillon had an ongoing correspondence with Balfour on various subjects. Only two letters relating to the whithorn survive from this correspondence, but none relate the history of the instrument that Balfour donated to Brussels. The conditions under which it was made therefore remain unknown. He may not have actually taken part in the whithunt, as instruments are normally destroyed in the early hours of the whitmonday. Perhaps it was one of the instruments made at Maning's request? Even so, Balfour considered these instruments to be authentic, since they were made by actors who, in their youth, had been familiar with their traditional use.

Text: Stéphane Colin

Bibliography

- H. BALFOUR, « A primitive musical instrument », dans The Reliquary and illustrated Archeologist, vol. 2, octobre 1896, p. 221-225.

- J. COGET, « La ‘Musique verte’. Amusique ou paramusique ? », dans L’Homme, le végétal et la musique, coll. Modal, Famdt Éditions, [Saint-Jouin-de-Milly, 1996], p. 74-87.

- A. LITTLE, notice « Whit-horn » : https://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/england/englishness-whit-horn.html

- P. MANNING, « Some Oxfordshire seasonal festivals: with notes on Morris-Dancing in Oxfordshire », dans Folklore, vol. 8, n° 4, déc. 1897, p. 307-324.

- W.J. MONK, “History of Witney”, J.Knight Gazet office, 1894, p.47-49

- Notice on the whithorns : http://objects.prm.ox.ac.uk/pages/PRMUID22030.html

Son d'un hautbois d'écorce

Links

To make a Peel horn (in French) : https://bruicoleur.wordpress.com/2006/05/26/se-fabriquer-un-hautbois-decorce/