July 2025

Fig.1

Marimba de tecomates, Chichicastenango (Guatemala), end 19th - begin 20th century, inv. 2019.0012

Fig.2

Bolange, Sierra Leone, before 1882, inv. 0670

Fig.3

Marimba de tecomates, Chichicastenango (Guatemala), end 19th - begin 20th century, inv. 2019.0012

Fig.4

K’iche’ musician playing a marimba de tecomates à Chichicastenango, © Robert Garfias

Fig.5

Manza of the Zande people in the RDC at the beginning of the 20th century. MIM, inv. 3220

Fig.6

Marimba players in Antiqua, Guatemala, 17 Novembre 2007, © Greg & Annie / Flickr

Fig.7

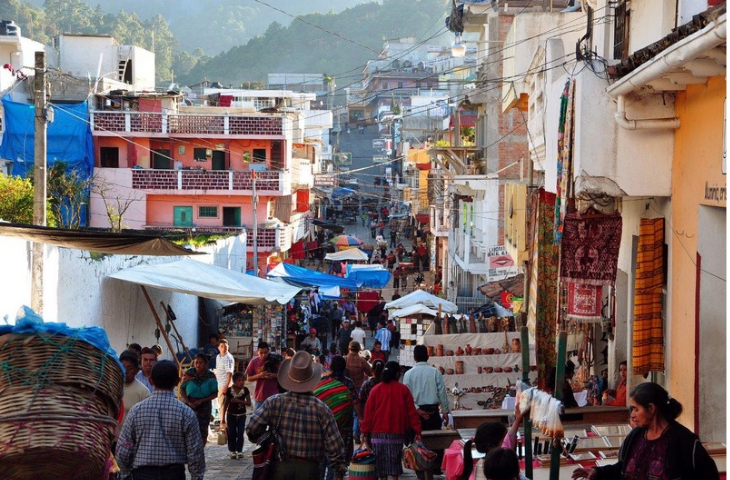

Chichicastenango market, 2009, © Chensiyuan / Wikimedia

Fig.8

Marimba de tecomates, Chichicastenango (Guatemala), end 19th - begin 20th century, inv. 2019.0012

A Marimba from Guatemala with African roots

This marimba de tecomates (also called marimba de arco) from Guatemala has been part of the MIM’s American musical instruments collection since April 2019. In the early 1980s, this instrument, measuring one and a half meters in length, was brought to Belgium by expats (fig.1).

Although the instrument is closely linked to Guatemala’s Indigenous Maya culture, its African origins are unmistakable. Like the West African balafon or the Congolese manza, it features a single row of tuned wooden slats, each suspended above a gourd resonator, all held within a wooden frame (fig. 2). Each slat corresponds to one gourd.

The instrument is constructed entirely without nails or glue. Plant fiber cords and small wooden pegs hold the frame together. Small holes were bored into the gourds and originally covered with pig gut membranes, secured with beeswax, to create a buzzing sound effect (charleo) - a feature also found on instruments like the bolange from Sierra Leone (fig.2). Traces of wax are still visible on the slats, where it was also used to fine-tune their pitch.

An instrument of the Maya tradition

This type of marimba has a wooden arc or arch attached to it, allowing the performer to sit beneath the instrument while playing (fig.3). A one-legged wooden support at the front helps keep the marimba balanced (fig.4). A similar playing position can be seen in the early 20th-century manza of the Zande people in northeastern Congo (fig.5). The arc of the MIM’s marimba was sawn off at a later stage, likely to make the instrument easier to transport.

The marimba de arco is among the earliest types of marimbas known in Central America. The MIM’s example has 24 keys and the same number of gourd resonators - one beneath each slat, typical for this type of marimba. Traditionally, the marimba de tecomates is played solo during ritual or ceremonial events. The performer plays relatively simple melodies in traditional rhythmic patterns. Originally tuned in pentatonic or heptatonic scales, under European influence the tuning gradually shifted toward a diatonic scale.

From Africa to Guatemala

Research shows that African marimbas were introduced to the Americas via the Pacific coastal regions of Costa Rica and Nicaragua and gradually made their way into the Guatemalan highlands. Colonial archives from the 17th and 18th centuries document the importation of large numbers of enslaved Africans to Guatemala, primarily to work on indigo plantations. The marimba de tecomates became deeply embedded in Maya culture. Indigenous musicians still see the instrument as part of their ancestral heritage. Playing the marimba remains a spiritual act - an act of communion with the ancestors.

As early as 1680, historical sources mention that the marimba was being played by Indigenous communities in the multi-ethnic settlements (pajudes) around Santiago de los Caballeros, the old capital of Guatemala. According to musicologist Sergio Navarrete Pellicer, the early adoption of the marimba by Indigenous societies is “a testimony to the early cultural and racial mixing of African, Spanish, and Indian populations.” In the pajudes, dance, music, and song were shared in moments of both celebration and devotion. These cultural exchanges created fertile ground for the development of a uniquely Indigenous variant of the marimba - African in origin, European in repertoire, Indigenous in performance. By 1769, the marimba (alongside the caramba, or mouth bow) had come to be seen as an instrument played exclusively by Indigenous people.

[1] Navarrete Pellicer, Maya Achi, p. 74

Colonial bans and national appropriation

To colonial authorities, Indigenous musical events were seen as signs of lingering “pagan” beliefs. The gatherings were condemned for their perceived profanity, interracial and intersexual dancing, and alcohol use - all considered immoral and contrary to colonial religious values. The diatonic marimba thus became part of an outlawed tradition. Indigenous communities, however, continued to build and play their marimbas in secret. These instruments were made clandestinely and played during underground rituals. As recently as 1981, the Guatemalan government still banned Indigenous musical gatherings.

Nevertheless, in 1978 the marimba was declared Guatemala’s “National Instrument” – 17 October became the official Día Nacional de la Marimba. Out of a romantic and exoticized vision of the ancient Indigenous cultural heritage, the politically dominant Ladino elite appropriated the instrument as a symbol of the country’s national identity, appealing to an assumed identification with the ancestral Maya – which stands in stark contrast to the second-class status that Indigenous people still occupy in contemporary Guatemalan society.[2] The African roots of the instrument are entirely ignored in this process of cultural appropriation. In fact, the “national” marimba is not the ancient diatonic marimba de tecomates. From the 18th century onwards, the diatonic version underwent “technical advancement.” The chromatic marimba has two keyboards and is played by more than one musician. The gourds were replaced by wooden or metal resonators. With up to 78 keys (marimba grande), this “wooden piano” proved adaptable to classical and popular European genres, fashionable in salons and ballrooms.

Today, this chromatic version is often played in luxury hotels in urban settings by musicians dressed in traditional Indigenous costumes, catering to tourists (fig.6). As Navarrete Pellicer observes: “Much of the twentieth-century cultural nationalism was motivated by the need to construct an external image of a colourful and attractively distinctive Indigenous Guatemala to attract tourists” (fig.8).[3]

[2] Navarrete Pellicer, Maya Achi, pp. 78-79

[3] Navarrete Pellicer, Maya Achi, p. 238

The MIM example

The marimba de tecomates (inv. 2019.0012) in the MIM collection is a traditional, diatonic Indigenous instrument that was likely built and used in secret, as part of a long-standing ceremonial tradition. By the 1970s, it was on display in the window of an antiques shop at the market of Chichicastenango, a town in the Guatemalan highlands (fig. 7). It caught the eye of a Belgian expat, who acquired the instrument.

Forty years later, the marimba entered the MIM collection, together with a huipil (a traditional smock-like garment), another marker of Indigenous identity (fig. 8).

Text: Saskia Willaert

Bibliography

- Navarrete Pellicer, Sergio, Maya Achi. Marimba Music in Guatemala, Philadelphia, 2005

- Neustadt, Robert, ‘Reading Indigenous and Mestizo Musical Instruments: The Negotiation of Political and Cultural Identites in Latin America’, Music and Politics i/2 (2007). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mp/9460447.0001.202/--reading-indigenous-and-mestizo-musical-instruments?rgn=main;view=fulltext (accessed 8 January 2019)

Audio & vidéo

- Marimba Ladino : https://www.muziekweb.nl/Link/KHX2047/Chapinlandia-Marimba-music-of-Guatemala

- Music in Guatemala: Musical Instruments of Mesoamerica, dir. Alfonso Moises, 2015 (from 14’02”) : https://filmfreeway.com/790186