An ambitious plan

At the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, probably toward the very end of 1899, Victor-Charles Mahillon, curator of the Instrumental Museum of the Royal Conservatoire in Brussels, conceived the project of building a “collection of graphophone cylinders reproducing popular music from different countries” (Archives MIM, Correspondance Mahillon). From January 1900 onwards, he traveled extensively in search of phonograph recordings: in Brittany (Quimper and then Vannes), London, Istanbul, Madrid, Dublin, Java, Tokyo, Peking, Calcutta, and elsewhere.

The creation of a collection of sound recordings dedicated to the world's popular musical traditions is remarkable in its precocity. It coincided with the Phonogrammarchiv project initiated by the Academy of Sciences in Vienna and the Musée Phonographique designed by Léon Azoulay for the Société Anthropologique de Paris. However, while these two projects integrated instrumental music into a broader program focused primarily on ethnographic and linguistic objectives, Mahillon’s project placed instrumental music at the center, using the phonograph as a tool for musicological and organological documentation. In this respect, it predates by several years the famous Phonogramm-Archiv created at the Berlin Institute of Psychology by Carl Stumpf and Erich Moritz von Hornbostel.

A project between notation and documentation

In a culture where notation was seen as the primary means of conveying music, Edison’s phonograph, patented in 1877, took several years to establish itself as a true musical medium. Until the late 19th century, the documentation of oral musical practices depended largely on transcription, often arranged for piano. Mahillon himself initially envisioned documenting the musical traditions associated with his collection of instruments solely through scores accumulated in the Special Library of the Instrumental Museum.

The only early alternative was the music box (inv. 1946) donated by the Bengali rajah Sourindro Mohun Tagore in 1881. Mahillon claimed it allowed one “to get an absolutely exact idea of the true character of the Hindu melody and to substitute for the cold interpretation of the notation the feeling of the author himself” (Écho musical, 12 January 1882).

The creation of a sound recording collection, particularly of instrumental music, thus represented a major conceptual shift for Mahillon. Notably, he did not include the Indian music box in his inventory until the very end of the 19th century, almost two decades after its acquisition (Catalogue, vol. 3, 1900). In other words, this music box, initially perceived as a device for recording Indian music, became a musical instrument simultaneously with the phonograph’s adoption as a tool for music reproduction.

Yet, the phonograph did not fully replace the piano score as a musical medium. Certain requests for “cylinders reproducing popular music—either vocal, mainly instrumental, or instrumental and vocal together” specified that, in the last two cases, the music “should be played on the original instruments and not reproduced on the piano, which would diminish its value.” Mahillon thus linked singing to an abstract melodic dimension—notation—while striving to document the timbre of instruments, which cannot be captured in transcription.

The assembly of the phonographic collection

The conditions enabling Mahillon’s paradigm shift are not fully clear. Although he seems not to have had direct contact with the initiators of the phonographic archives in Vienna, Paris, or Berlin, several factors likely influenced him. Firstly, the acquisition at the end of 1899 of a graphophone with various cylinders via the patron Louis Cavens was probably decisive (Archives MIM, Correspondance Mahillon). Secondly, shipments of cylinders from Calcutta (Tagore rajah), Tianjin (Edouard Closson), and Peking (Jules Van Aalst) must have raised awareness (Annuaire, 1900). Notably, these shipments coincided with Chinese recordings by Paul Georg von Möllendorff offered by Robert Hart to Léon Azoulay (Bulletin de la Société d'Anthropologie, 1900/1, 1902/3). As Hart, Möllendorff, and Van Aalst were colleagues in the Chinese customs administration, it is likely Mahillon learned of this project through his friend Van Aalst.

To assemble his collection, Mahillon employed the same strategies he used for acquiring instruments, mobilizing personal contacts, Belgian diplomatic networks, and commercial distribution. Initially, he facilitated the purchase of recording equipment for correspondents in Calcutta, Java, Tokyo, and Peking. Later, he diversified intermediaries, contacting production companies like the Columbia Company, merchants distributing cylinders, and private individuals capable of recording music themselves. Some offers, however, were refused due to cost, such as a collection of rural “oriental music” cylinders offered by Checri-Saouda in May 1900.

The resulting collection was heterogeneous, comprising commercial, domestic, and field recordings.

A forgotten collection

Unlike the renowned phonographic archives in Vienna, Paris, and Berlin, the Brussels collection remained largely unknown, probably because it was part of a musical instrument museum and was never systematically inventoried. Its exact size and composition remain uncertain, though a 1942 inventory noted “forty-eight graphophone cylinders recording exotic music” (inv. 3590), suggesting it never reached the scale of other collections. Partial dispersal occurred through loans during the early 20th century, such as Indian recordings used in a play in May 1900 (Gerothwohl) and “five rolls of recordings of exotic music” loaned in December 1943 and not returned the following year (De Bock).

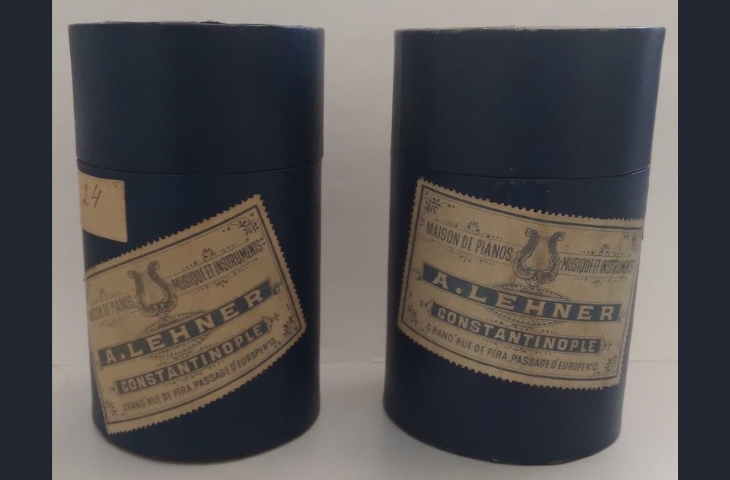

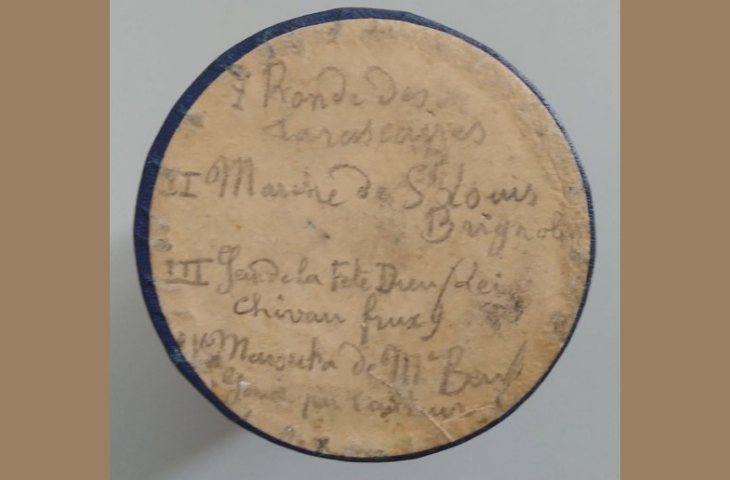

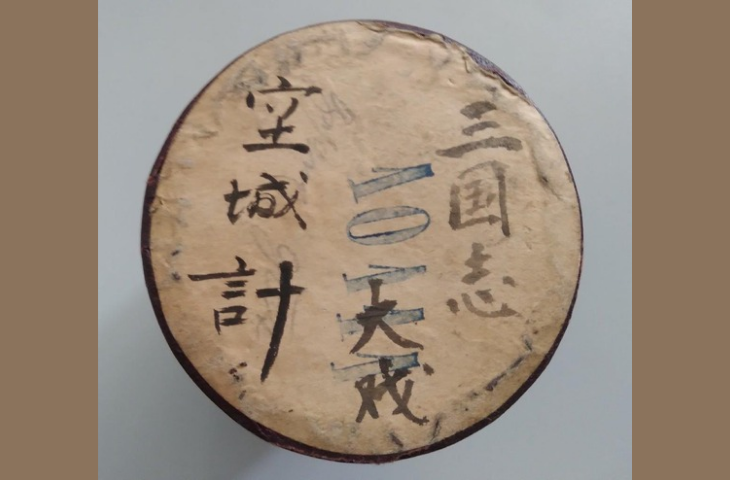

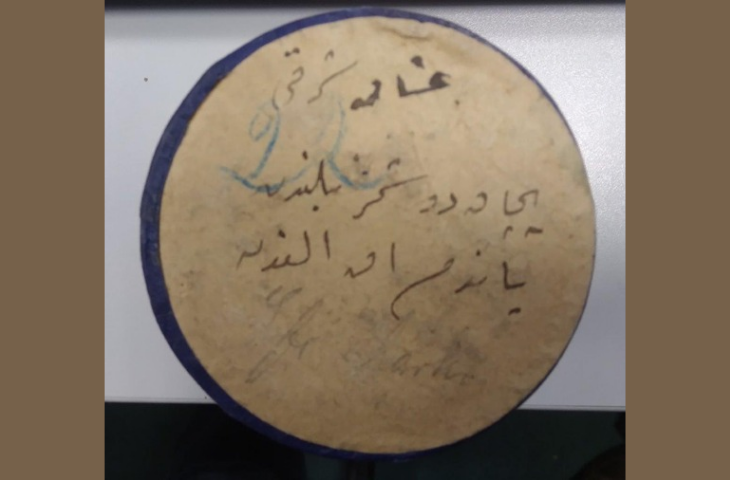

The rediscovery of forty-three wax phonograph cylinders in the MIM reserves, mostly in their original boxes, has allowed part of this forgotten collection to be reconstituted. Alongside a continuous numbering system (1 to 43) are inscriptions indicating older, now incomplete sub-collections, with origins including Provence, Egypt, China, India, the Ottoman Empire, England, and North America. Some match Mahillon’s correspondence, confirming they were part of his late-19th-century sound archives project. Cylinders were often unbranded but occasionally came from companies like Edison Bell or Columbia, or local distributors such as Lehner in Istanbul or Bevans & Co in Calcutta.

While a full inventory and digitization of the collection are ongoing, a few records illustrate its immense value: galoubet, music from popular and religious festivals in Provence, Ottoman repertoire and rebetiko from Istanbul, Peking opera and Chinese popular songs, and classical music from Egypt.

Author of the study: Fañch Thoraval