February 2025

Fig.1

Harpischord, Vincent Tibaut, Toulouse, 1679, inv. 0553

Fig.2

Harpsichord (name board and signature), Vincent Tibaut, Toulouse, 1679, inv. 0553

Fig.3

Mirror frame, Noel Hache, Toulouse, 17th century, © BLB Antic, Versailles

Fig.4

Harpsichord (soundboard and keyboard), Vincent Tibaut, Toulouse, 1679, inv. 0553

Fig.5

Harpsichord (rose), Vincent Tibaut, Toulouse, 1679, inv. 0553

Fig.6

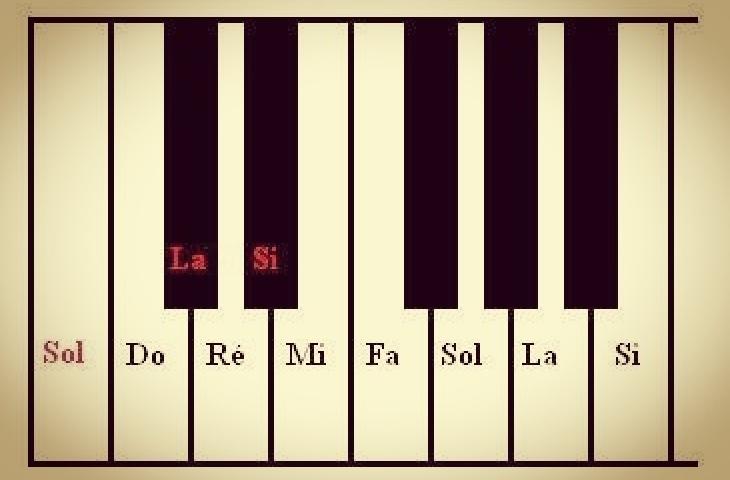

Example of a short octave, Wikipedia

Fig.7

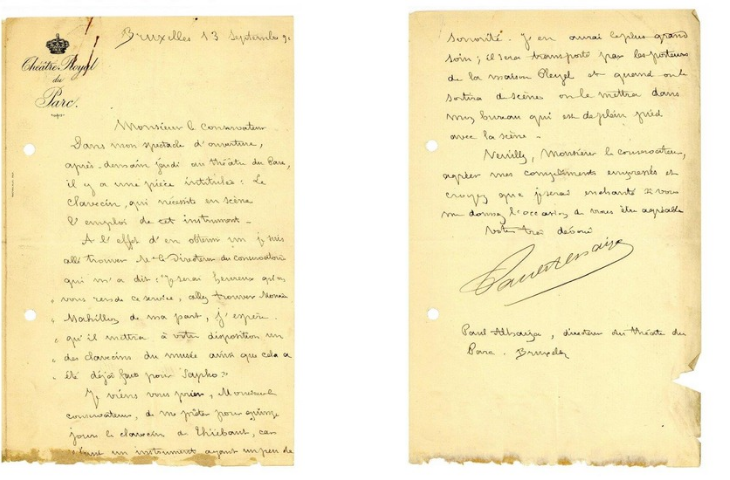

Loan request of the Tibaut harpsichord, September 13, 1897

The harpsichord by Vincent Tibaut in the MIM

Of the three surviving harpsichords by Vincent Tibaut, the one in the MIM (inv.553, fig.1), dated 1679, is the oldest. The other two, from 1681 and 1691, are in France, in the private collection of Yannick Guillou and the Musée de la Musique in Paris respectively. As French harpsichords from the 17th century are rare pieces, it is exceptional that Tibaut should have left three of them! The Brussels harpsichord was acquired by the museum in 1879, along with a large part of the Tolbecque collection.

A life marked by loss

Thanks to Florence Gétreau's research, little is known about the life of Vincent Tibaut. The son of a master carpenter from the Nantes region, he was born around 1647. He moved to Toulouse no later than 1673, when a document mentions him as a journeyman carpenter in that city. That same year, he married Peyronne de Saint-Victor, who gave him five children, only one of whom reached adulthood. Peyronne herself died in 1685 and Vincent Tibaut quickly remarried Gabrielle Manianac, aged 23. Four more children were born to this union, at least one of whom died in infancy. A life punctuated by the rhythm of death, like many other lives in those days. Tibaut himself died six years later, leaving a 29-year-old widow with three young children and four more from his first marriage. No doubt she had to organise her survival, as she rented out a property whose income would help her to support her numerous offspring.

A cabinetmaker with a distinctive style

Curiously, none of the documents referring to Tibaut mention him as a harpsichord maker, only as a carpenter and then cabinetmaker. Moreover, the milieu he seems to have frequented is more closely linked to the world of craftsmen and people of dress than to musicians or instrument makers. Was harpsichord making a sideline for him, insufficient to support himself? It is true that Louis XIV did not create a specific guild for instrument makers in the French provinces until 1679. But this does not entirely explain the absence of any mention of this trade.

Another surprising point is the fact that on notarial deeds Vincent Tibaut is unable to sign his name, whereas all three of his harpsichords have a magnificent marquetry signature on the name board (fig.2). The quality of the marquetry is what distinguishes the MIM instrument from its two brothers. The sides and lid are made of walnut veneered with various types of wood forming flowers, leaves and birds. The lid also bears a magnificent coat of arms, as yet unidentified but no less indicative of a high-ranking patron. In addition, the letter ‘M’ appears all around the instrument, under the keyboard and the case. This type of vegetal decoration with light motifs on a dark background is typical of Toulouse furniture from this period, as can be seen from mirror frames produced in the city (fig.3). Comparing them with the decoration on the harpsichord in the MIM highlights Vincent Tibaut's skill as a cabinetmaker. His shadings, in particular, are delicate to produce, giving the plants intense relief and life. To complement this decoration, the soundboard is painted with brightly coloured flowers (fig.4).

Construction, features and use

The construction of Tibaut's three harpsichords bears many similarities and reflects a variety of influences, but is essentially close to the Lyon school in its many similarities with Italian construction. For example, the address bar, which is not aligned with the top of the body but slightly below it, the thin ribs, the fact that the ribs are fitted around the back rather than on top of it, the body frame, etc.

The instrument's keyboards have four octaves and a fourth from G/Si to C (52 notes), including a short octave in the basses (fig.4). A short octave consists of removing certain altered notes from the lower part of the keyboard. The lowest notes (the black keys on our piano: C# and Eb) are given a different note (A and B, fig.6). But here the short octave is produced by split sharps, i.e. the key is divided in two, with one part giving the short octave and the other the traditional notes. This shows Tibaut's particular interest in playing the lowest notes. However, in the French harpsichord music published at the time, the lower notes, and the short octave in particular, are rarely used. We might therefore conclude that Tibaut's interest in the short octave had more to do with the practice of unwritten music and improvisation, which was widely practised at the time, than with written music, which does not reflect this usage.

Originally, the two keyboards were coupled simply by pulling or pushing back the lower keyboard, whose two cheeks (side pieces surmounted by a lion) are worked so that they can be easily manipulated.

Since its entry into the Musée Instrumental, as it was known at the time, the instrument has been played several times, which means that over time it has undergone transformations to its original structure in order to remain usable. Liszt, in particular, took to its keyboard during his visit to Brussels in 1881. It was also loaned out for performances outside the museum, including at the Théâtre Royal du Parc for a play entitled ‘Le clavecin’, and then for ‘Sapho’, performed by the French actress Gabrielle Réjane, in 1897. It is amusing to note how quickly the instrument was delivered. The theatre director sent the loan request to Victor-Charles Mahillon, then director of the Musée des instruments de musique, just two days before the performance (fig.7)! The instrument was transported by the theatre and kept safe for the duration of the performances in the director's personal office, on the same level as the stage. This kind of loan could never happen nowadays, given the great danger of moving such an ancient and exceptional heritage.

Text: Stéphane Colin

Bibliography

- GETREAU, Fl., « Vincent Tibaut de Toulouse, ébéniste et facteur de clavecins. I. Données biographiques », dans Musique, images, Instruments. Revue française d’organologie et d’iconographie musicale, n°2, 1996, p. 197-202

- ANSELM, A., « Vincent Tibaut de Toulouse, ébéniste et facteur de clavecins. II. Bref regard sur trois clavecins de Vincent Tibaut », dans Musique, images, Instruments. Revue française d’organologie et d’iconographie musicale, n°2, 1996, p. 203-209

- HUBBARD, F., « Le clavecin. Trois siècles de facture », Paris, Laget, Librairie des Arts et Métiers, 1981, p. 73-75