Fig.1

Hwang-chông-tché, Brussels, Mahillon, ca. 1890, inv. 0865

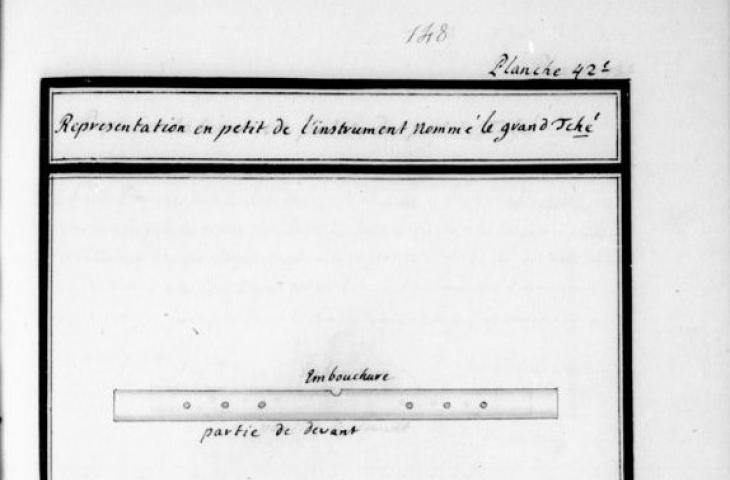

Fig.2

Joseph Amiot, Mémoire sur la musique des Chinois, tant anciens que modernes, 1776, © gallica.bnf.fr / Département des manuscrits

Fig.3

Lü, Brussels, Mahillon, ca. 1890, inv. 0860

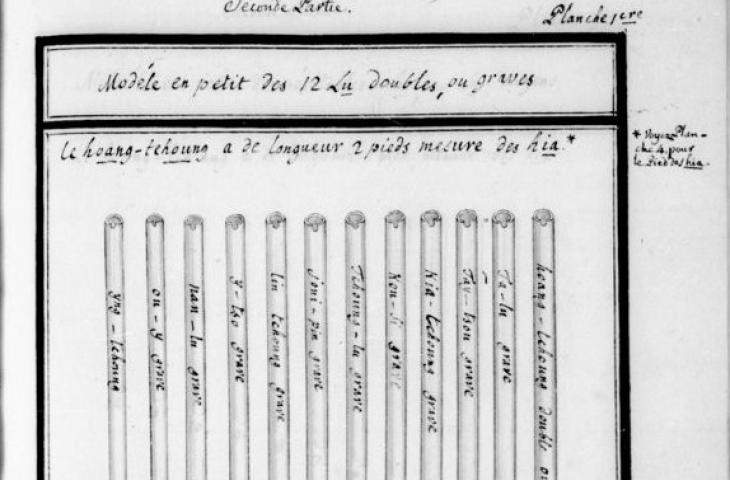

Fig.4

Joseph Amiot, Mémoire sur la musique des Chinois, tant anciens que modernes, 1776, © gallica.bnf.fr / Département des manuscrits

Fig.5

Portrait of Victor-Charles Mahillon (1841-1924)

Fig.6

Joseph-Marie Amiot, engraving from the book Galerie illustrée de la Compagnie de Jésus d'Alfred Hamy, 1893

Victor-Charles Mahillon, the founder and first curator of the Musée instrumental du Conservatoire Royal de Musique (known today as MIM), wanted to acquire the widest possible range of instruments existing in all parts of the world. One of his aims was to study their acoustics.

Mahillon also had copies of instruments that he was unable to acquire for the museum and which he borrowed from another collections. Being a wind instrument maker himself, it was easy for him to have this work done by competent personnel.

When this possibility did not exist either, Mahillon tried to base himself on texts. He used the work of a Jesuit in Peking to reconstruct Chinese flutes and standards. Five instruments in our Chinese collection are the result of this work.

Jesuits working in China in the 18th century studied various aspects of Chinese civilisation and passed on their knowledge in letters sent to Europe. Some letters were published and thus reached a wider audience. Joseph-Marie Amiot (1718-1793) is known among these clerics for his writings on Chinese music, but also, for example, for having composed a Manchu-French dictionary (the then reigning Qing dynasty was of Manchu ethnicity).

Arriving in 1751 in Peking, where he spent the rest of his life, Joseph Amiot sent in 1776 a manuscript in French, published in 1779 in Paris under the title Mémoire sur la musique des Chinois, tant anciens que modernes. This manuscript and its edition can be consulted on the website of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

A large part of Amiot's work is devoted to Chinese music theory and instrument descriptions. The precise descriptions including proportions and the engravings reproducing the main drawings of the manuscript allowed the reconstruction of the objects that most interested Victor Mahillon.

Chinese music is pentatonic, but Chinese music theory described very early the twelve semitones of the scale. These twelve notes gave rise to the creation of standards in the form of tubes of different lengths (lü).

The numbers 0859, 0860, 0861 in our inventory are the reconstruction of 3 lü corresponding approximately to E♭ an octave apart. These are wooden tubes with a notch at one end to facilitate the production of sound, and a plug at the other. The lü built for Mahillon are made of wood; in theory, however, they represent the sound of bamboo, a plant absent from Europe.

Amiot also describes a very strange flute reproduced by Mahillon under n° 0865 and 0866. Amiot himself reproduces the very precise description made by prince Tsai-Yu in 1596 of an instrument examined in an antique shop. It is a transverse flute whose blowing hole is located in the middle of the tube and not near one of the ends as it is universally made. On each side of this central hole, but at an angle of 90°, there are three equally spaced playing holes. Amiot tells that both ends are closed, whereas the reconstructions by Mahillon are open at both ends.

Text: Claire Chantrenne